by Michael F. Mascolo, Ph.D.

The key to fostering the development of moral behavior in children is to help children build a bridge between self-interest and concern for others. Children and adults who act in morally exemplary ways are those who have formed a “moral identity” – a sense of self in which concern for the welfare of others plays a central role. Such individuals gain a sense of self-satisfaction by being committed to a moral code. They measure themselves in terms of what they can do for others, and not in terms of what others can do for them.

All of us – children included – can be torn by two different sets of motives. One is self-interest or concern for the self. For example, people act out of self-interest when they pursue food out of hunger and thirst; pursue their own personal goals, seek fame and fortune and so on. The other motive is concern for the other. We act out of concern for the other when we help other people; share our food; visit the sick; or otherwise act for the benefit of other people. A concern for the other is the basis of all forms of moral  conduct. If it were not for the presence of other people, moral concerns would not ordinarily arise.

conduct. If it were not for the presence of other people, moral concerns would not ordinarily arise.

When we think of these two classes of motives, we ordinarily think that (a) one class of motives – self-interest – is more natural than the other (concern for the other); and (b) they are antagonistic to each other – that is, self-interest necessarily conflicts with concern for the other. Neither of these two everyday beliefs is true. Humans are both self-interested and concerned about others. Infants as young as 8-months of age show empathic concern for others in pain; begin to help other people when needed and show related behaviors.

It is true that self-interest is often in conflict with concern for others. However, this is not necessarily the case. In fact, it is likely that finding ways to help children bring self-interest together with concern for others is the key to fostering the development of a moral sense. Teens and adults who are morally exemplary (who act in the service of others) are those for whom morality is a central part of their identity. In other words, they identify themselves – their self-interest – with the interests of others.

Reconciling “Self-Interest” with “Concern for Others”

How do we develop as moral persons? We often think that being moral involves denying self-interest. We think that the natural condition of children (or humans in general) is to be self-interested. If this is true, then to be moral – to act out of care for others – we must suppress or repress what we want for ourselves. But again, this is not necessarily so.

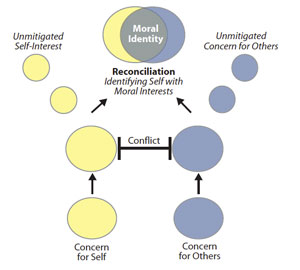

When children are very young, self-interest and concern for others tend to be separate. In some situations, children act out of self-interest. For example, if Todd wants a toy, he may simply grab it from Lexi. If, on another occasion, Todd sees Lexi crying when her toy breaks, Todd might attempt to comfort Lexi, fix her toy for her or give her another toy. Children tend to switch from self-interest to concern for others from moment to moment. In the figure below, this stage of development is shown by the separate yellow and blue circles representing self-interest and concern for others (at the bottom of the figure).

Over time, as children become older (say, from age 6 or 7 and beyond), self-interest and concern for others will come into conflict. That is, they will begin to become aware of times in which self-interest seems to compete with concern for others. For young children, if there is a conflict between self-interest (Todd wants the toy) and concern for others (Lexi wants the same toy), in most (but not all) situations, most (but not all) young children will take the path of self-interest. Soon, however – especially when adults call it to children’s attention – children become aware of the conflict between self-interest and concern for others. They can begin to see, “If I take the toy, I’ll get what I want; but if I take the toy, my friend will be sad – what should I do?”

Over time, as children become older (say, from age 6 or 7 and beyond), self-interest and concern for others will come into conflict. That is, they will begin to become aware of times in which self-interest seems to compete with concern for others. For young children, if there is a conflict between self-interest (Todd wants the toy) and concern for others (Lexi wants the same toy), in most (but not all) situations, most (but not all) young children will take the path of self-interest. Soon, however – especially when adults call it to children’s attention – children become aware of the conflict between self-interest and concern for others. They can begin to see, “If I take the toy, I’ll get what I want; but if I take the toy, my friend will be sad – what should I do?”

This is shown in the middle of the figure on the next page. What’s important here is how children reconcile the conflict between self-interest and concern for others over time. The question for parents becomes “How can I help my child see that acting out of concern for others can actually enhance his sense of self?” The answer is to guide your child through the process of acting out of care and concern for others, and then to reflect together on what this means for your child. Over the years, hundreds and even thousands of opportunities for doing this will present themselves:

When a four-year old grabs a toy from his sister, ask, “how do you think that makes her feel”? What can you do to make her feel better?

Even young children are capable of helping out in family chores. Consider having a time during the day or during the week where the entire family pitches in to complete the family chores. Make it something the family does together. This is how children gain a sense of community and helping within the family.

Point out circumstances when family members are in need of help. This could be as simple as helping bring the dishes to the kitchen after a meal, or as complex as bringing a meal to a sick relative; helping an older relative clean out her basement, or, for older children, helping to take care of a sick child. Volunteer with your child at a local homeless shelter or food kitchen. Talk explicitly and concretely about why you are doing this. Don’t just say that you are “helping others”, but point out how specific things that you are doing (e.g., distributing food) are helping specific people that your child sees. Talk openly about how your child feels about working at the shelter. Talk about what it feels like to want to be out with friends (self-interest) and to also want to help others who are in need. Talk about why it is important to want to act out of concern for others – even when it would be easier not to.

After hundreds of opportunities that present themselves over the years, children will gradually come to see that acting out of concern for others can be an important part of their identity. This is shown at the top part of the figure that accompanies this article. At this point, self-interest and concern for others come together. Moral concerns (concerns about others) become central to the adolescent’s sense of who he or she is. Morality and self-interest need not compete for attention – to consider the needs of others becomes part of what makes me me.

As shown in the figure above, developing a moral identity is not the only path that a child can take. If children do not find ways to bring together moral concerns with concerns for the self, their development can take the path toward, on the one hand, predominance of self-interest, or, on the other, a predominance of concern for others. Neither of these options is particularly healthy. Unmitigated self-interest, of course, breeds antisocial behavior. Unmitigated concern for others involves a denying of the self and the needs of the self. Neither is sustainable in life. The key is to help children develop a sense of self in which moral concerns do not complete with self-interest, but instead come to be seen as something that completes the self.

When forging a moral identity, adolescents come to identify themselves with the goal of caring for others. Instead of seeing concern for others as something that is at odds with self-interest, they will come to see that acting out of care for others can be part of who they are. They will have forged a moral identity and will become more likely to act out of a sense of purpose rather than simply out of a sense of self-interest.