|

We all know what Goldilocks was looking for as she sampled the three bowls of porridge made by Mother Bear: Not too hot, not too cold, but just right. Like anything, when helping our children adjust to emotional situations, getting it “just right” is easier said than done. Happily, however, we don’t have to get it “just right” all the time. Instead, we simply need to get it “just right” most of the time. Happier still, giving “just the right” emotional guidance is more a matter getting to the “right range” than finding any single fixed point.

Carmen is doing her math homework. It’s hard. In frustration, she repeats, “I can’t do it! This is stupid! I can’t do it.” She throws her pencil down. “I’m never gonna be able to do this! Why do I need to know this?”

Carmen is in a vulnerable state. What is at stake is her developing sense of self. How do we respond to her? Just like Goldilocks, we want to avoid the extremes of pushing too much or not pushing enough. We want to get it just right. But how do we know what’s just right? This can be very difficult. A good place to start, however, is with your child’s emotions. If we want children to be able to manage their own emotions, we have to start by modulating and managing their emotions for them, and then gradually, as they become more emotionally competent, turning the task of emotional management over to the children themselves.

Supporting Children through Moderate Levels of Challenge

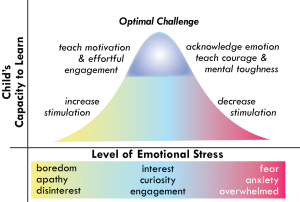

Like all of us, children cannot learn well under conditions of intense, strong or overwhelming emotion. However, the opposite is also true – children cannot learn if they not emotionally aroused enough. Children learn best – including learning how to cope with their own emotions – under in contexts in which adults provide and support children through moderate levels of challenge.

This idea is shown in the figure that accompanies this article. The shows what happens to children’s capacity to learn under conditions of increasing levels of emotional challenge. As shown in the figure, if the level of challenge provided to a child is too high, they will experience a range of negative emotions, such as frustration, anger, sadness, embarrassment, shame and so forth. If the child’s emotion is genuine, this is a signal to reduce the level of challenge and stimulation provided to the child.

However, under such circumstances, it is not be helpful to reduce the level of challenge to zero! In order to learn, children must be emotionally aroused and engaged. If we reduce the level of challenge and stimulating too much, the child will become bored, apathetic, disinterested, or perhaps even disrespectful or nonchalant! This is not a formula for learning or for emotional development. If the child’s level emotional engagement in a task is too low, it may becomes necessary to increase the challenge and level of stimulation given to the child.

The key is to find a moderate level of challenge and stimulation – not too much, not too little, but just right for the task at hand in the situation at hand. When children are provided with moderate challenge, they become more alert, engaged, interested, and curious. When you are able to consistently provide children with moderate levels of challenge, children learn that you will be sensitive to their emotional needs. However, they will also learn that you mean business: When something is difficult, we don’t just crawl in a corner and pout. We face it – initially with support, and thereafter increasingly on our own — in an attempt to learn from the situation.

Teaching Emotional Management through Moderate Challenge

If Carmen is experiencing difficulty with her math, she will be frustrated, angry and perhaps demoralized. In this situation, she is not going to be able to learn. Again, the goal of the adult in such a situation is to modulate the level of challenge in the situation to make it more intellectually and emotionally manageable for the child.

Once Carmen’s emotions have been brought to a more manageable state, it is time to start teaching – not just the math, but also about emotional management. We learn what we do — not simply what we are told — and particularly what we do under the guidance of others. Thus, when you break down the math problem for the child; hold the child to attainable standards of perseverance, manage the child’s frustration en route to success; and so forth, you are teaching not only the practical skill in question (e.g., math), but also the essential skill of managing emotions.

If the child’s level of motivation and emotional engagement begin to wane, the adult has to make a judgment. Is the child getting too tired? If so, it may be time to stop and revisit the issue later on. If not, it may be time to provide guidance and instruction on the need to increase one’s level of alertness, attention and effort in the task. Is the child getting overwhelmed? If so, perhaps it’s time to take a break. But what if the adult makes the judgment that the child is capable more, but simply has not yet built skills to manage frustration or difficult emotion? If that is so, it might be necessary to set the bar a bit higher. An adult might choose to offer guidance and instruction about the need for “mental toughness” or even “courage” in the process of working through difficult tasks. After all, to encourage is to foster “courage” (i.e., “en-courage”) as one deals with difficult tasks and events.

It is not always easy to make judgments about what a child’s emotional capacity. Such judgments are more art than science, and are heavily dependent on how well an adult knows a child, their relationship history, and the adult’s values. What’s more, a child’s capacity to manage emotion in difficult situations will change not only as he or she develops, but will also be different in different tasks and situations, even at different times of the day! However, we don’t have to get it right every time. As long as we make consistent, good faith efforts to strike the delicate balance between emotional nurturance and emotional challenge, we almost can’t help but to get it “just right” more often than not.